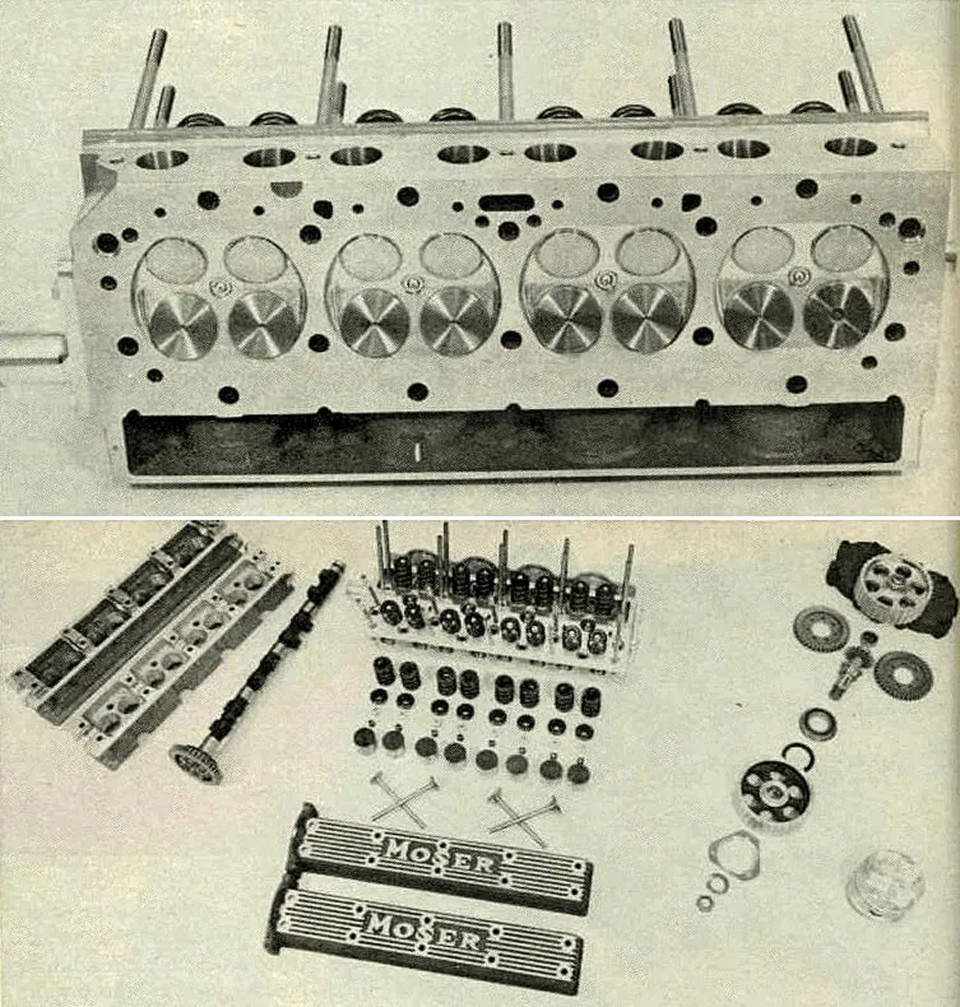

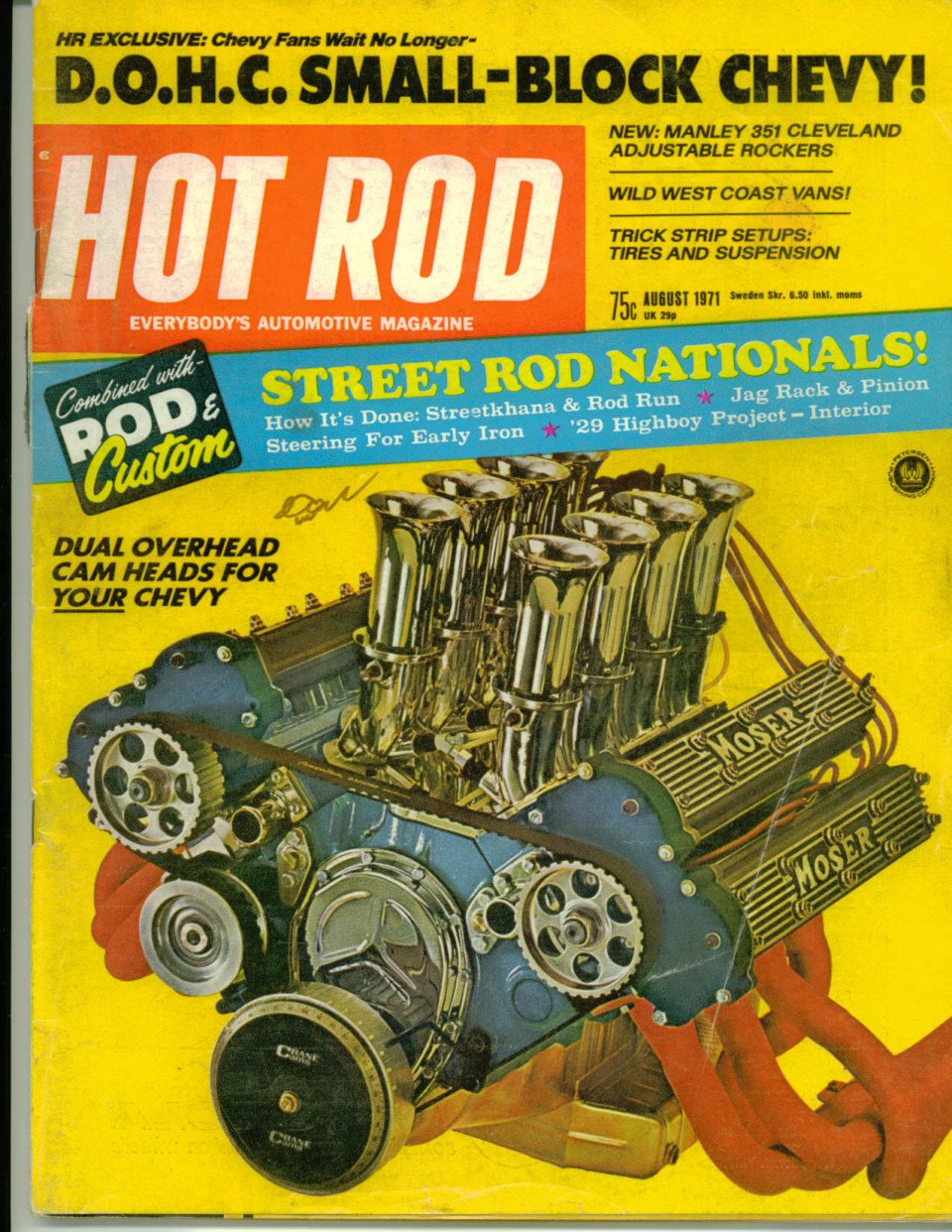

Who would have thought that in 1965, a gentleman, Richard Moser, working for Chrysler would start a quest to build a dual-overhead-cam (DOHC) engine that would be part of a Chevrolet history? At first, he thought the 340 would be a great platform. However, it did not take long for a change in direction of the concept, and his design found use on the small-block Chevy.

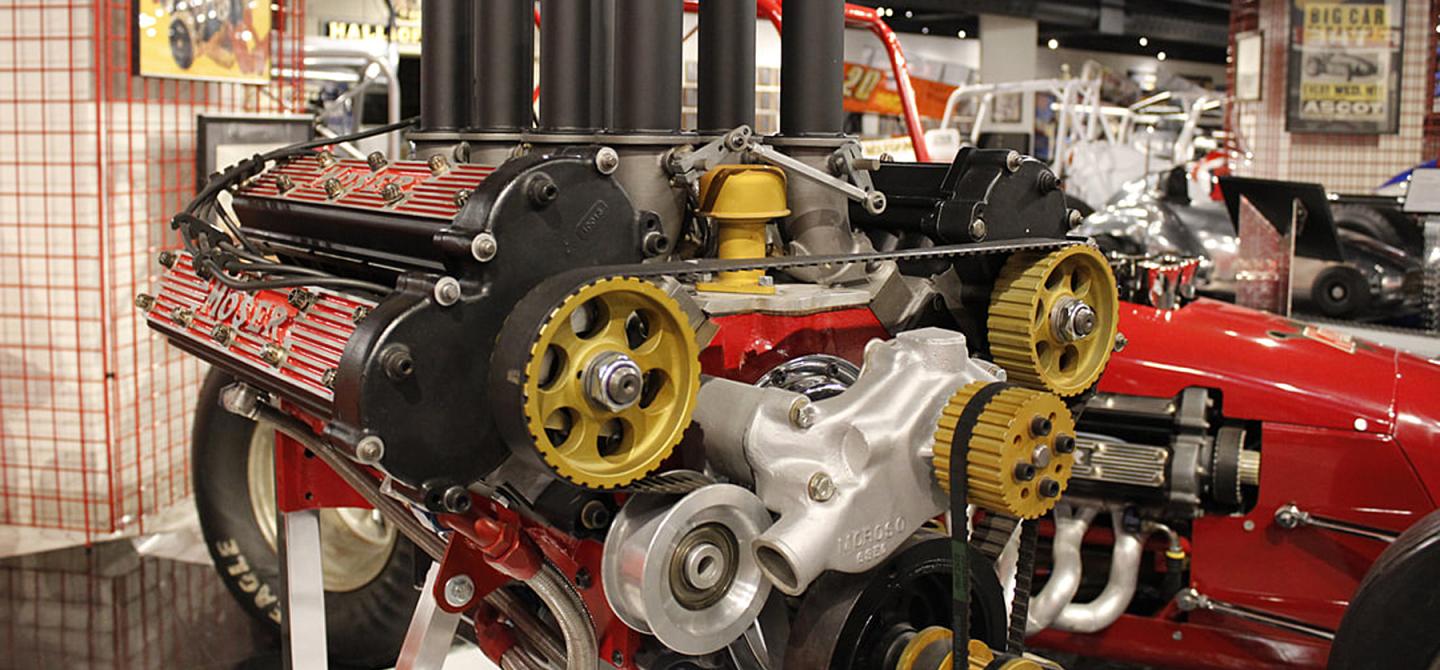

According to a 1971 article in Hot Rod magazine (HRM), when the plan got underway, he teamed with Crane Cams’ founder, Harvey Crane Jr. Harvey was a staunch proponent of the DOHC design, and the two men teamed up to get the project underway. As you can surely imagine, it took a lot of engineering to get four valves to fit within the confines of the cylinder head, and the cylinder itself. In fact, early designs implemented two exhaust ports for each cylinder. Talk about a mess of tubes for headers! Anyway, testing soon confirmed the elimination of the extra exhaust ports offered no substantial loss of power.

Attaching the heads to any small-block Chevy engine block was easy, as the factory bolt holes are utilized. However, four additional holes did need to be drilled in each bank to accommodate additional bolts.

When it was time to adjust the valves, things got interesting. The overhead cams also eliminate rocker arms, so how would one adjust the valves if needed? According to the HRM article, valve adjustment is accomplished with the use of shims (sourced from Jaguar) being inserted into the valve retainers.

A camshaft is a camshaft, correct? Not in this application. The cams are actually hollow, and the lobes are drilled to allow oil to lubricate valvetrain components. The Crane-designed cams featured 250 degrees of duration at .050-inch and .450-inch lift on both intake and exhaust lobes. At first, a chain and gears were thought to be the best way to drive the cams. It did not take long until a Gilmer belt was incorporated to reduce cost. The heads underwent two years of development before they were ready to unveil to the public.

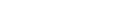

The Moser engine is a prominent display in a sea of cool items. (Engine images courtesy of the American Museum of Speed)

While the heads lent themselves to high-RPM racing applications, they could, in theory, be used on a street car. In fact, one of these small-block wonders found its way into a famous ’32 Ford roadster built by Tom McMullen. You can read about the car here.

The DOHC Moser heads did find their way onto many race cars — mostly dirt track Sprint cars and in fact, one of those engines was placed into a Sprint car that is now in the Speedway Motors Museum of American Speed. The car was raced in the Champ series and the small-block under the hood comes in at a small 305 cubic inches.

The Museum of American Speed has one of these engines prominently displayed for all to see, and we asked about its origins. The display engine was not run in the previously mentioned Speedway Champ car but was purchased at an auction. Unfortunately, the museum didn’t receive any hard facts about its history. It is still a great addition to the museum.

It is believed that roughly 30 sets of heads were created, but there are no guesses as to how many actually made it to market. Regardless, it is rare items like these that are found in the museum that make it a place every gearhead needs to visit. So, might I suggest you take a look at the Museum of American Speed’s website and plan your next trip around a visit to this iconic collection of hot rods, race cars, and memorabilia.